Unique Games Conjecture

Very recently, Subhash Khot won the Rolf Nevanlinna Prize, considered one of the top honours in the field of mathematics, for his contribution to computational complexity theory. The conjecture has broad applications in the theory of hardness of approximations and is unusual in the sense that unlike  problem, the academic world seems evenly divided on whether this conjecture is true or not.

problem, the academic world seems evenly divided on whether this conjecture is true or not.

“Some very natural, intrinsically interesting statements about things like voting and foams just popped out of studying the UGC…. Even if the UGC turns out to be false, it has inspired a lot of interesting math research.”

—Ryan O’Donnell

This post is very basic and targeted towards anyone who has a knowledge of what complexity classes  ,

,  ,

,  Hard and

Hard and  Complete means.

Complete means.

Assuming  , researchers started exploring footholds for finding near optimal solutions efficiently. However, as it turns out, for some

, researchers started exploring footholds for finding near optimal solutions efficiently. However, as it turns out, for some  Complete optimization, it is not possible to approximate beyond a particular factor. Perhaps an example will highlight point.

Complete optimization, it is not possible to approximate beyond a particular factor. Perhaps an example will highlight point.

Approximation Algorithms

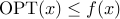

Any  optimization,

optimization,  , is either a minimization or a maximization problem. For a minimization problem, for each instance

, is either a minimization or a maximization problem. For a minimization problem, for each instance  of

of  , there exists a non-empty feasible set of solutions each of which is assigned an objective value. Our goal is to come up with the one whose objective value is lowest. Let's us call such a solution as optimal solution and let's denote it value by

, there exists a non-empty feasible set of solutions each of which is assigned an objective value. Our goal is to come up with the one whose objective value is lowest. Let's us call such a solution as optimal solution and let's denote it value by  . We wish to come up with a solution which is as close (but greater since

. We wish to come up with a solution which is as close (but greater since  is a minimization problem) to

is a minimization problem) to  as possible. Suppose, an approximation algorithm

as possible. Suppose, an approximation algorithm  outputs a solution which at most

outputs a solution which at most  times

times  (

( ). We say that

). We say that  is a

is a  factor approximation algorithm. Similar results hold for maximization problems as well.

We will now prove the hardnes for TSP.

factor approximation algorithm. Similar results hold for maximization problems as well.

We will now prove the hardnes for TSP.

Example: Travelling Salesman Problem (TSP)

We will show that it is hard to approximate TSP for any approximation factor. To prove this, we will transform Hamiltonian Cycle Problem to TSP.

TSP: Given a weighted undirected graph, find the minimum weight tour that visits each vertex exactly once.

Hamiltonian Cycle Problem: Given a Graph  , does there exist a simple cycle that visits all the vertices of

, does there exist a simple cycle that visits all the vertices of  exactly once?

exactly once?

Given an instance  of Hamiltonian Cycle Problem, construct an instance

of Hamiltonian Cycle Problem, construct an instance  of TSP as follows:

of TSP as follows:

.

. is a complete graph.

is a complete graph.For all edges

,

,  .

.For other edges,

where

where  .

.

If  has a hamiltonian cycle,

has a hamiltonian cycle,  . Otherwise, the tour must include an edge of weight

. Otherwise, the tour must include an edge of weight  . Hence,

. Hence,  .

.

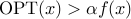

If there is a  factor approximation factor for TSP, we can reduce Hamiltonian Cycle Problem to TSP and check the decidability of Hamiltonian Cycle Problem. If

factor approximation factor for TSP, we can reduce Hamiltonian Cycle Problem to TSP and check the decidability of Hamiltonian Cycle Problem. If  has a hamiltonian cycle,

has a hamiltonian cycle,  . Hence, the algorithm outputs a tour of weight at most

. Hence, the algorithm outputs a tour of weight at most  . Otherwise,

. Otherwise,  which implies the tour the algorithm outputs has weight greater than

which implies the tour the algorithm outputs has weight greater than  . This creates a gap between the YES/NO instances of Hamiltonian Cycle Problem and it's decidability can be checked efficiently, which is not possible. Hence, it's hard to approximate TSP to a factor of

. This creates a gap between the YES/NO instances of Hamiltonian Cycle Problem and it's decidability can be checked efficiently, which is not possible. Hence, it's hard to approximate TSP to a factor of  , for any

, for any  .

.

Reduction

Let  be a minimization problem. A gap-introducing reduction maps an instance

be a minimization problem. A gap-introducing reduction maps an instance  of SAT to a instance

of SAT to a instance  of

of  such that

such that

If

is satisfiable, then

is satisfiable, then  , and

, andIf

is not satisfiable, then

is not satisfiable, then  .

.

Obviously,  . Such a kind of gap-introducing reduction immediately implies an inapproximability of

. Such a kind of gap-introducing reduction immediately implies an inapproximability of  for

for  .

.

One problem with the above approach is blowing an “additive” gap to a “multiplicative” gap.

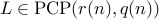

PCP Theorem

Probabilistic characterization of  class yields a general technique for gap-introducing reduction. Informally speaking, a probabilistically checkable proof for an

class yields a general technique for gap-introducing reduction. Informally speaking, a probabilistically checkable proof for an  language is a proof whose validity can be checked probabilistically by examining its very few bits. A probabilistically checkable proof system comes with two parameters: (a)

language is a proof whose validity can be checked probabilistically by examining its very few bits. A probabilistically checkable proof system comes with two parameters: (a)  the number of random bits required by the verifier, and (b)

the number of random bits required by the verifier, and (b)  the number of bits of the proof the verifier is allowed to examine.

the number of bits of the proof the verifier is allowed to examine.

A language  if there's a verifier

if there's a verifier  that on input

that on input  , obtains a random string of length

, obtains a random string of length  and queries

and queries  bits of the proof such that (

bits of the proof such that ( &

&  are constants):

are constants):

If

, then there's a proof which verifier accepts with probability

, then there's a proof which verifier accepts with probability  , and

, andIf

, then every proof is accepted with probability

, then every proof is accepted with probability  .

.

The PCP Theorem gives another characterization of the class  .

.

PCP Theorem:

One direction of the proof,  is easy (try proving it as a small exercise). Other direction has been a result of years of research by various CS Theorists. For an excellent exposition to the history of PCP Theorem, refer here. Fortunately, the theorem, modulo its proof, is sufficient to derive hardness results.

is easy (try proving it as a small exercise). Other direction has been a result of years of research by various CS Theorists. For an excellent exposition to the history of PCP Theorem, refer here. Fortunately, the theorem, modulo its proof, is sufficient to derive hardness results.

Hardness of MAX-3SAT

In this example, we will try proving the hardness for  . The reduction is from

. The reduction is from  . Specifically, there exists a constant

. Specifically, there exists a constant  such that a

such that a  formula

formula  can be converted to a

can be converted to a  formula

formula  such that

such that

If

is satisfiable, then

is satisfiable, then  , and

, andIf

is not satisfiable, then

is not satisfiable, then  .

.

The PCP for  consists of a truth assignment to its boolean variables. The essential idea of the reduction is to encode the probabilistically checkable proof as a

consists of a truth assignment to its boolean variables. The essential idea of the reduction is to encode the probabilistically checkable proof as a  instance. The verifier uses

instance. The verifier uses  random bits and queries

random bits and queries  bits of the proof. In all, there can be

bits of the proof. In all, there can be  different possible random strings generated and hence a total of

different possible random strings generated and hence a total of  locations of the proof can be queried by the verifier.

locations of the proof can be queried by the verifier.  will have a variable corresponding to each of these locations.

will have a variable corresponding to each of these locations.

A random string  picked by the verifier gives us a value either True or False based on the values of the variables in those

picked by the verifier gives us a value either True or False based on the values of the variables in those  locations. This truth value can be represented as a function

locations. This truth value can be represented as a function  . Hence, we can define a

. Hence, we can define a  boolean formula

boolean formula  as follows: for all

as follows: for all  such that

such that  , add a clause

, add a clause  where

where  are the corresponding variables and

are the corresponding variables and  if

if  and

and  otherwise. Then can at most be

otherwise. Then can at most be  clauses in

clauses in  . Also, the length of each clause is

. Also, the length of each clause is  . Ensure that the length of each clause is

. Ensure that the length of each clause is  by adding

by adding  new variables to each clause. The maximum number of clauses now is

new variables to each clause. The maximum number of clauses now is  .

.

.

.  has at most

has at most  clauses. If

clauses. If  is satisfiable, all the clauses of

is satisfiable, all the clauses of  is true. However, if

is true. However, if  is not satisfiable, at least half the random string rejects the proof i.e. at least half of

is not satisfiable, at least half the random string rejects the proof i.e. at least half of  are not satisfiable. Hence, number of unsatisfiable clauses in

are not satisfiable. Hence, number of unsatisfiable clauses in  must be at least

must be at least  . Hence,

. Hence,  .

.

PCP Theorem was a landmark result in the field of computational complexity and after its inception, the focus moved on to produce optimal results i.e. to prove approximability and inaproximability results for a problem that match each other. The most influential development consisted of  (a.k.a.

(a.k.a.  ), Raz's Parallel Repetition Theorem, introduction of Long Code, its application in analyzing PCPs, and Hastad's use of Fourier Series to analyze Long Code. I will briefly mention about these results.

), Raz's Parallel Repetition Theorem, introduction of Long Code, its application in analyzing PCPs, and Hastad's use of Fourier Series to analyze Long Code. I will briefly mention about these results.

Label Cover Problem (a.k.a. 2-Prover-1-Round Game)

A ![textup{2-Prover-1-Round Game } mathcal{U}_{2p1r}(G(V,W,E),[m],[n],{pi_e|e in E})](eqs/8797519014191334089-130.png) is a CSP.

It consists of a bipartite graph

is a CSP.

It consists of a bipartite graph  where vertices represent variables and edges represent constraints. Goal is to find a labelling

where vertices represent variables and edges represent constraints. Goal is to find a labelling ![L : V to [m], W to [n]](eqs/5039911781225843550-130.png) such that for all edges

such that for all edges  , the following “projection” constraint is satisfied:

, the following “projection” constraint is satisfied:  . Let

. Let  denote its optimal value.

denote its optimal value.

![textup{OPT}(mathcal{U}_{2p1r}) := max_{L:V to [m], W to [n]} frac{1}{|E|} cdot |{e in E ~ | ~ L satisfies e}|](eqs/2534395284399738719-130.png)

I will now give the game formulation of  Given an instance

Given an instance  , consider a probabilistic verifier

, consider a probabilistic verifier  which picks an edge

which picks an edge  at random and sends

at random and sends  to Prover

to Prover  and

and  to Prover

to Prover  . The provers respond back with labels from set

. The provers respond back with labels from set ![[m]](eqs/8209412804294245610-130.png) and

and ![[n]](eqs/8209412804297245475-130.png) respectively. The Verifier accepts only if

respectively. The Verifier accepts only if  where

where  and

and  are the labels returned. The provers’ strategy is to maximize the probability of acceptance. The probability, called the value of the game, will obviously be same as

are the labels returned. The provers’ strategy is to maximize the probability of acceptance. The probability, called the value of the game, will obviously be same as  . This establishes the analogue between Constraint Satisfaction View and the

. This establishes the analogue between Constraint Satisfaction View and the  Prover

Prover Round view.

Round view.

We are interested in the case when the label sets ![[m]](eqs/8209412804294245610-130.png) and

and ![[n]](eqs/8209412804297245475-130.png) have constant sizes. The PCP Theorem implies that the gap version of

have constant sizes. The PCP Theorem implies that the gap version of  is

is  Hard and this gap can be amplified using Raz's Parallel Repetition Theorem.

Hard and this gap can be amplified using Raz's Parallel Repetition Theorem.

PCP Theorem + Raz's Parallel Repetition Theorem

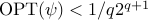

For every  ,

,  is

is  Hard for instances with label cover of size

Hard for instances with label cover of size  . Specifically, there exists a constance

. Specifically, there exists a constance  such that for every

such that for every  ,

, ![mathcal{U}_{2p1r}(G(V,W,E),[m],[n],{pi_e|e in E})](eqs/1537798539578299191-130.png) ,

,  , it is

, it is  Hard to distinguish between:

Hard to distinguish between:

case:

case:  .

. case:

case:  .

.

Many inapproximability results are obtained by reduction from  .

.

The inapproximability results derived from  often use gadgets constructed from Boolean hypercube. These reductions can be viewed as PCPs and the gadgets test, probabilistically, whether a given codeword is a Long Code or not. A useful Long Code-ing scheme is the so called dictatorship function on a boolean hypercube - it's a function

often use gadgets constructed from Boolean hypercube. These reductions can be viewed as PCPs and the gadgets test, probabilistically, whether a given codeword is a Long Code or not. A useful Long Code-ing scheme is the so called dictatorship function on a boolean hypercube - it's a function  that depends only on one coordinate i.e.

that depends only on one coordinate i.e.  for some fixed

for some fixed  . The truth table for this function can be thought of as an encoding scheme for

. The truth table for this function can be thought of as an encoding scheme for  . We need that a dictatorship function passes this test with probability

. We need that a dictatorship function passes this test with probability  whereas a function that is far from bring a dictatorship function passes this test with probability at most

whereas a function that is far from bring a dictatorship function passes this test with probability at most  . This gap

. This gap  essentially translates to a

essentially translates to a  instance of

instance of  .

.

The PCP replaces every vertex of  with a boolean hypercube: for

with a boolean hypercube: for ![mathcal{U}_{2p1r}(G(V,W,E),[m],[n],{pi_e|e in E})](eqs/1537798539578299191-130.png) , every

, every  is replaced by a

is replaced by a  dimensional hypercube and every

dimensional hypercube and every  is replaced by a

is replaced by a  dimensional hypercube. The PCP consists of truth table of boolean functions on these hypercubes. PCP testing consits of two parts:

dimensional hypercube. The PCP consists of truth table of boolean functions on these hypercubes. PCP testing consits of two parts:

Codeword Testing: Each boolean function is close to a dictatorship function, and

Consistency Testing: For an edge

,

,  , where

, where  and

and  are the labels which the dictatorship function on boolean hypercubes for vertex

are the labels which the dictatorship function on boolean hypercubes for vertex  and (respectively)

and (respectively)  correspond to.

correspond to.

Unique Games Conjecture

The PCP strategy described above succeeds for some problems ( ,

,  ,

,  ), it doesn't yield any useful results for problems such as

), it doesn't yield any useful results for problems such as  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . For the first set of problems, PCPs are allowed to make three or more queries but for the second set of problems, at most two queries are allowed, which makes the PCP very weak.

. For the first set of problems, PCPs are allowed to make three or more queries but for the second set of problems, at most two queries are allowed, which makes the PCP very weak.

It was pointed out that another barrier is the “many-to-one”-ness of the projection constraints  in

in  , i.e., when

, i.e., when  . This poses a problem in the consistency testing part where a

. This poses a problem in the consistency testing part where a  query PCP is too weak to ensure consistency between two hypercubes of vastly varying dimensions. This motivated the study of

query PCP is too weak to ensure consistency between two hypercubes of vastly varying dimensions. This motivated the study of  where

where  and

and ![pi_e: [m] to [n]](eqs/4954899951486397777-130.png) is a bijection.

is a bijection.

Unique Game

A

![mathcal{U}(G(V,E),[n],{pi_e|e in E})](eqs/90946154902823104-130.png) is a constraint satisfaction problem: given a directed graph

is a constraint satisfaction problem: given a directed graph  where vertices represent variables and edges represent constraint, the objective is to assign a label to each vertex from the set

where vertices represent variables and edges represent constraint, the objective is to assign a label to each vertex from the set ![[n]](eqs/8209412804297245475-130.png) such that maximum number of edges are satisfied. The constraint on each edge

such that maximum number of edges are satisfied. The constraint on each edge  is a bijection

is a bijection ![pi_e:[n] to [n]](eqs/2578720891533161573-130.png) . An edge

. An edge  is satisfied by a labelling

is satisfied by a labelling ![L:V to[n]](eqs/8245891505432492545-130.png) if

if  .

.

![textup{OPT}(mathcal{U}) := max_{L:V to [n]} frac{1}{|E|} cdot |{e in E ~ | ~ L satisfies e}|](eqs/2948692338437000110-130.png)

As opposed to  , the graph here need not be bipartite. This distinction is minor as can be seen by the following game formulaion of

, the graph here need not be bipartite. This distinction is minor as can be seen by the following game formulaion of  : given an instance

: given an instance ![mathcal{U}(G(V,E),[n],{pi_e|e in E})](eqs/90946154902823104-130.png) of

of  problem, the verifier picks an edge

problem, the verifier picks an edge  at random and sends

at random and sends  to prover

to prover  and

and  to prover

to prover  .

.  &

&  returns a label in

returns a label in ![[n]](eqs/8209412804297245475-130.png) and the verifier acceptes only if

and the verifier acceptes only if  where

where  &

&  are the answers of two provers.

are the answers of two provers.

Note that if  , then such a labelling can be found in polynomial time: fixing the label of a vertex automatically fixes the label of every vertex which is its neighbour and so on. From the viewpoint of

, then such a labelling can be found in polynomial time: fixing the label of a vertex automatically fixes the label of every vertex which is its neighbour and so on. From the viewpoint of  , the interesting case is when

, the interesting case is when  where

where  .

.

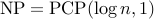

Unique Game Conjecture

Unique Games Conjecture:  is

is  Hard

Hard

For every  , there exists a

, there exists a  , such that given a

, such that given a  instance

instance ![mathcal{U}(G(V,E),[n],{pi_e|e in E})](eqs/90946154902823104-130.png) , it is

, it is  Hard to distinguish between the two cases:

Hard to distinguish between the two cases:

case:

case:  .

. case:

case:  .

.

Note that the conjecture is false if  . Also, a random assignment satisfies

. Also, a random assignment satisfies  fraction of edges and hence

fraction of edges and hence  .

.